Supreme Shift: What the 6-3 Conservative Majority Means Going Forward

12.16.2020

It was a year of momentous decisions followed by the loss of an iconic justice. The immediate past term saw the Supreme Court address an unusually high number of consequential, politically charged issues. The Court rendered historic rulings on presidential immunity and accountability, free exercise of religion, LGBTQ rights, abortion rights, jury trial rights, the insanity defense, and other pressing, “hot-button” issues. Then, shortly before the start of the new term, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the leader of the liberal wing of the Court, passed away. Her seat was filled within a few weeks by the speedy nomination and confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett, then a Judge on the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, who was a strong favorite of politically conservative groups.

What is the significance of “liberal” Ginsburg being replaced by “conservative” Barrett? Although predictions are difficult to make with any confident precision, what generalized impact can nevertheless be expected?

“Liberal” Justices, “Conservative” Justices

Before going forward, it is important to be clear about the usage, here and in judicial studies generally, of the terms “liberal” and “conservative.” Those terms are not used in the sense of so-called judicial “activism” versus “restraint.”[1] They are not used as labels for judicial decision-making on the basis, or not, of “originalism;”[2] deference to the elected, more democratic branches and the states;[3] “textualism;”[4] stare decisis;[5] or any other variously articulated interpretive methodology advocated as a limit on judicial discretion and policy-making.[6]

Rather, they are used to identify patterns, social and political, reflected in the decisions and votes of judges and the courts on which they sit. This is especially true and revealing when considered over the course of ideologically charged “hot-button,” issues. These are the issues where, for example, “conservative” Republican politicians and voters would typically support one position, while “liberal” Democratic politicians and voters would typically support the other.

Anyone who follows politics and courts can surely identify a list of such issues. Among the most salient are those dealing with the separation of church and state, gun rights, LGBTQ rights, abortion, affirmative action, immigration, the death penalty, business regulation, and in recent years, just about anything involving President Obama or Trump. Regardless of any avowed decision-making methodology, the most insightful and candid judicial realists, both on and off the bench – Oliver Wendell Holmes, Benjamin Cardozo and, more recently, Richard Posner, among the most prominent – have described, yes, the realities of how judges decide.

Holmes spoke of the unfortunate “aversion” of most judges to confront the actual non-legalistic reasons for their decisions. This reluctance, he complained, merely “leave[s] the very ground and foundation of judgments inarticulate, and often unconscious.”[7] Cardozo acknowledged much the same.[8] He also emphasized that the underlying values that actually do direct a judge’s decisions ultimately succumb to analysis. As he put it:

There is in each of us a stream of tendency, whether you choose to call it philosophy or not, which gives coherence and direction to thought and action. Judges cannot escape that current any more than other mortals.[9]

Accordingly, when labeling judges, their decisions, and patterns as “liberal” or “conservative,” it is this “stream of tendency. . . . which gives coherence and direction” to their overall records to which judicial scholars – and even casual court observers – are referring. It is that, and not the felicitous and much less reliable characterizations as “activist” versus “restraintist,” “originalist” versus “non-originalist,” etc.[10]

The Blockbuster Past Term – with Ginsburg

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg did not claim to be an originalist or textualist or strict constructionist or other species of purported judicial restraintist – or the opposite. But regardless of how she or others might characterize her approach to decision-making, she was, in terms just discussed, unquestionably “liberal.” This manifested itself emphatically in the many momentous decisions that marked the Court’s past term. A quick review of a few of these illustrates the point.

In both cases involving presidential accountability, Justice Ginsburg voted with the majority to reject President Trump’s claims of immunity from investigative subpoenas.[11] Although the vote in both cases was 7–2, there was a bare 5–4 majority that refused to subject subpoenas from state investigations to a heightened or strict scrutiny before requiring a president to respond.[12] Ginsburg cast one of the essential votes for that ruling.

In the major abortion rights case of the term, it was another bare majority that invalidated Louisiana restrictions on procedures and personnel involved in providing services.[13] Ginsburg again cast one of the decisive votes to reject the restrictions as an “undue burden” on the right to choose. That bare majority with Ginsburg’s vote was a repeat of the previous term’s decision to issue a temporary stay.[14]

The 5–4 voting was identical in last term’s case involving DACA (Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals).[15] That bare majority rejected the Trump administration’s attempt to repeal the Obama administration’s program of forgoing deportation procedures against undocumented immigrants who entered the country as children. It was hardly surprising that Ginsburg would vote to thwart the effort to undo a compassionate immigration policy. She joined Chief Justice Roberts’s majority opinion that castigated the Trump administration’s “post-litigation rationalization” for what it tried to do.[16] Likewise, Ginsburg cast a necessary vote the previous term to join another Roberts 5–4 majority opinion, similarly rejecting the Trump administration’s “contrived reasons” for attempting to insert a citizenship question on census forms.[17]

In several politically charged cases, Justice Ginsburg actually joined opinions authored by conservative Trump appointee Neil Gorsuch. Each time, however, Gorsuch had written for the Court’s politically liberal result. In one truly landmark case, Gorsuch’s opinion for the 6–3 majority construed the 1964 Civil Rights Law’s prohibition against “sex” discrimination in hiring as applying to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.[18] While such an interpretation might have been surprising coming from self-proclaimed “originalist” Gorsuch,[19] it would have been even more surprising if liberal Ginsburg had not supported the result.

Ginsburg also aligned with Gorsuch in enforcing an 1832 Treaty with the Creek Nation against the state of Oklahoma.[20] Ginsburg joined Gorsuch’s 5–4 majority opinion to hold that, despite a history of violations, the treaty barred Oklahoma from exercising criminal jurisdiction over Creek Indians within that large swath of the state that had been pledged to the Creek Nation. In the previous term, Ginsburg was also with Gorsuch, this time in a 5–4 majority opinion by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, to protect the hunting rights of the Crow Tribe against restrictions, otherwise applicable under Wyoming law, by enforcing an 1868 Treaty.[21]

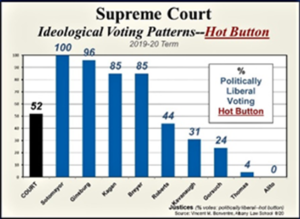

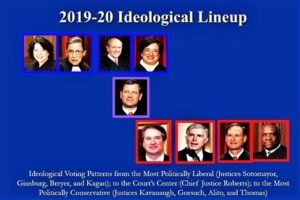

Of course, Justice Ginsburg was not always on the winning side of Supreme Court decisions. In fact, in the divided decisions last term, she was in the majority less often than most of her colleagues.[22] On the other hand, her votes virtually always supported the liberal side in those cases having a clear political or social dichotomy – i.e., 96% of the time, or in all but one of 27 cases that can fairly be characterized as such.[23] Indeed, in the rather clear ideological divide among the justices, Ginsburg’s record for her final term on the Court placed her at the near-perfect end of the liberal spectrum. (See graph: Ideological Voting Patterns—Hot Button, 2019-20 Term—Politically Liberal Voting.)

When Ginsburg passed away on September 18, 2020, the Court lost the liberal icon who had served for 27 years.

Ginsburg to Barrett

In an order issued near the end of last term, a 5–4 majority of the Court – Chief Justice Roberts, together with the four liberal justices: Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan – upheld pandemic restrictions in California. The attendance and other limitations, as applied to churches, had been challenged as violations of religious free exercise.[24] Roberts, in a separate opinion responding to the conservative dissenters – Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh – defended the restrictions as reasonable public health measures about which the Court “lacks the background, competence, and expertise. . . . and is not accountable to the people.”

Less than one month following Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation to fill the Ginsburg vacancy, the Court rendered another 5–4 decision on similar restrictions.[25] The line-up was mostly the same. But Ginsburg’s death reduced the liberal justices to three, and Barrett’s appointment expanded the conservatives – even without Chief Justice Roberts—to five. The per curiam opinion, joined by the dissenters in the previous case plus Barrett, invalidated New York’s pandemic restrictions on the ground that churches were treated more harshly than other activities. Roberts’ effort, to show again that the difference in activities justified the difference in treatment, was to no avail. With Barrett now in the Ginsburg seat, the previous 5–4 vote flipped.

It is foolhardy to extrapolate from a single vote in a single case, let alone be overly confident in predicting how a justice will eventually vote on a whole gamut of issues. But then-Judge Barrett had compiled a judicial record prior to her Supreme Court appointment. In a word, it was staunchly conservative. Notwithstanding the portrayals of her judicial philosophy – whether by supporters or opponents in the confirmation proceedings and elsewhere, or even by herself – her record is decidedly politically and socially conservative.[26]

While a complete survey of Barrett’s three-year record on the Seventh Circuit is beyond the scope of these few pages, a review of those most self-revealing opinions and votes – her dissents – is certainly possible. As judicial scholars, court watchers, and judges themselves best understand, these open disagreements with one’s colleagues – a veritable announcement to the public that “I lost,” that “I couldn’t persuade my colleagues,” and that “They are wrong” – are typically reserved for matters especially important to the dissenter. As esteemed New York jurist Hon. Hugh R. Jones put it in his venerable “Cardozo Lecture” delivered in 1979, dissents are “matters of high principle or instances of deep, irresistible visceral compulsion.”[27]

So, what did then-Judge Barrett deem to be sufficiently important or “matters of high principle” that she chose to disagree openly with her colleagues? In criminal justice cases, the answer seems clear. Her dissents were always against rulings that sided with the accused, the defendant on trial, or the inmate.

In one case,[28] the majority vacated a sentence as erroneously enhanced under the First Step Act of 2018.[29] Judge Barrett argued in dissent that a previous sentence, which had been vacated because illegally imposed, should still count as a predicate to support enhancement of the sentence in question. In another,[30] the majority ruled that a defendant’s motion to reconsider his sentence extended his time to appeal. Barrett dissented, arguing that the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure had overridden the leniency of the previous rule.

In a third criminal case,[31] Judge Barrett’s colleagues granted post-conviction relief because the prosecution had concealed evidence that the victim had been hypnotized to enhance his recollection. In dissent, while conceding the Brady violation,[32] Barret insisted that it was not so clearly a violation of established law to justify overturning a state court decision.[33] In yet another fair trial case,[34] Judge Barrett dissented when the majority granted habeas corpus to a defendant who had been questioned in camera, in an ex parte hearing, by the trial judge who barred defense counsel from participating. According to Barrett, there was no clear right to counsel violation, because the hearing did not qualify as a “critical stage” without the prosecutor’s presence.

Inmates fared no better with Judge Barrett. In a prisoner rights case,[35] the majority sustained an action alleging the use of excessive force in violation of Eighth Amendment rights. Inmates, who were bystanders to an already subdued scuffle, suffered injuries from ricocheting shots recklessly fired in their midst by guards. Judge Barrett dissented, viewing the guards’ actions as mere non-actionable “deliberate indifference” rather than malice.

The only case in which Judge Barrett dissented on the side of someone accused or convicted involved gun rights.[36] The majority rejected a Second Amendment challenge to federal and state laws that prohibit the firearm possession by convicted felons, particularly when the felonies “reflecting grave misjudgment and maladjustment.” Barrett complained, however, that “[f]ounding-era legislatures did not strip felons of the right to bear arms,” unless their crime actually demonstrated a public safety threat.

Again, the point is not right or wrong, wise or foolish, legally correct or not. It’s about the “stream of tendency.” And her dissents in these cases uniformly suggest that Judge Barrett’s tendency is politically conservative. The same is true for her dissents outside the realm of criminal justice.

The one immigration case in which Judge Barrett dissented is, perhaps, a compelling illustration.[37] The majority rejected a Trump administration regulation, promulgated by the Department of Homeland Security, that greatly expanded the category of inadmissible noncitizens as “public charges.” The regulation, which would bar anyone from entering the country who was “likely to receive public assistance in any amount, at any point in the future,” was held to be well beyond the bounds of the governing immigration statutory provisions.

In her lengthy and wide-ranging dissenting opinion, Judge Barrett acknowledged that the majority’s view was consistent with previous interpretations of the statutory provisions, that the regulations were widely viewed as “too harsh,” and that DHS had exaggerated its regulatory latitude. Nevertheless, Barrett argued that her self-described “unfortunately, excruciating” analysis of applicable immigration laws dictated deference to the agency. She insisted that a “clear-eyed” consideration of federal law shows that DHS’s expansive definition of “public charge” was not unreasonable.

Regardless of the merits of Judge Barrett’s ultimate conclusion, it might well be asked what “matter[] of high principle or instance[] of deep, irresistible visceral compulsion” – as Judge Jones put it in his Cogitations—compelled Barrett to publicly disagree with her colleagues? What drove her to engage in an “unfortunately, excruciating” analysis to take issue with her court’s more benign treatment of immigration-minded noncitizens? Whether Barrett’s analysis was more or less correct than the majority’s in this seemingly close case, one point cannot be denied. Her conclusion was the one favored by the Trump administration and, even more to the point, by political and social conservatives favoring restrictive immigration policies.

The very same political and conservative leanings are reflected in the two votes Judge Barrett cast to join the dissenting opinions of others—cases involving abortion. In light of the leanings displayed in her dissenting opinions, the positions she supported on the right to choose should not be surprising. In one case,[38] the majority denied an en banc reconsideration of a decision that had invalidated, as an “undue burden,” a mandatory ultrasound followed by an 18-hour waiting period prior to any abortion. Barrett joined the dissent. Similarly, the year before, when the majority declined another en banc reconsideration of a decision invalidating restrictions on pre-viability abortions,[39] Barrett joined the dissent that urged a narrower view of abortion precedents.

Those are then-Judge Barrett’s dissents – opinions and votes – on the Seventh Circuit. There is no exception among them from a social and political “stream of tendency.”

What Does All This Mean?

Reviewing their respective records suggests quite strongly that Justice Barrett will vote very differently than did Justice Ginsburg on issues with a clear liberal versus conservative divide. Even when limited to those specific cases discussed, it seems clear that Barrett will be much more supportive of gun rights, of accommodating religion, and of immigration restrictions. It is also clear that she will be less supportive of criminal justice rights, of abortion rights, and of interference with executive branch prerogatives – at least regarding socially and politically conservative policies.

Considering questions that Justice Barrett may well confront in her first term on the Court, as well as those she is already considering, the contrast between her likely positions and those taken by Justice Ginsburg is stark. A few illustrations make this evident.

In a clash between religious liberty and state laws prohibiting sexual orientation discrimination,[40] Justice Ginsburg’s consistent record supporting LGBTQ rights makes clear that she would support Washington’s anti-discrimination law. Justice Barrett’s already demonstrated support for religion over pandemic restrictions suggests she might take the opposite position.

In a pending case revisiting state restriction on abortion,[41] there is little doubt that Ginsburg would vote against Mississippi’s ban on abortion beyond the 15th gestational week. Based on Barrett’s past support for limiting abortions, it is likely that her vote would be different.

Among several Second Amendment cases percolating in courts below, a Third Circuit decision, over an ardent dissent by a Trump-appointed judge, upheld New Jersey’s ban on large-capacity magazines.[42] Again, there is little doubt how Justice Ginsburg would vote considering her past skepticism about gun rights.[43] On the other hand, Justice Barrett has favored those rights, even in dissent for convicted felons.

Among the immigration cases with pending certiorari petitions before the Court, a Ninth Circuit decision, over another dissent by a Trump-appointed judge, ruled that the expedited removal of a noncitizen without a hearing, despite a fear of persecution in his native country, violates due process.[44] Justice Ginsburg’s numerous pro-immigrant votes[45] almost assures that she would have supported the due process claim. Justice Barrett’s arduous dissent in support of the controversial immigration-restrictive “public charge” policy, by sharp contrast, makes her vote for the noncitizen less likely.

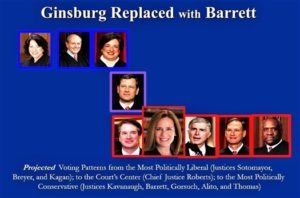

Of course, there are so many other areas of the law, even if confined to ideologically divisive “hot-button” issues, where Justice Barrett could be expected to vote differently than would Justice Ginsburg. Based on their respective records, as well as the fair characterization of a very liberal Ginsburg being replaced by a seemingly very conservative Barrett – combined with the records to date of the two previous Trump-appointees – it is indeed quite reasonable to presume that the ideological direction of the Court will undergo a significant shift. (See graphs: Ideological Voting Patterns—Hot Button, 2019-20 Term—Politically Conservative Voting; and Ginsburg Replaced with Barrett—Hot Button—Politically Conservative Voting.)

Vincent Martin Bonventre is the Justice Robert H. Jackson Distinguished Professor of Law at Albany Law School.

[1]. On the merits generally of judicial restraint versus activism, see Vincent Martin Bonventre, Judicial Activism, Judges’ Speech, and Merit Selection: Conventional Wisdom and Nonsense, 68 Alb. L. Rev. 557 (2005).

[2]. See, e.g., Antonin Scalia, Originalism: The Lesser Evil, 57 U. Cinn. L. Rev. 849 (1988–1989).

[3]. See, e.g., William H. Rehnquist, The Notion of a Living Constitution, 54 Tex. L. Rev. 693 (1976).

[4]. See, e.g., Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 507 (1965) (Black, J., dissenting) (Hugo Black rejecting the right to privacy as nowhere within the text of the Constitution).

[5]. See, e.g., June Medical Services LLC. v. Russo, 140 S.Ct. 2103, 2133 (2020) (Roberts, C.J., concurring) (Chief Justice Roberts voting with the majority, despite his earlier dissent on the same issue, on the basis of stare decisis).

[6]. See, e.g., The White House, Law & Justice, Supreme Court Nominee Amy Coney Barrett: “Judges Are Not Policymakers,” Sept. 29, 2020, (quoting then-Judge Barrett declaring, “A judge must apply the law as written. Judges are not policymakers”), https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/supreme-court-nominee-amy-coney-barrett-judges-not-policymakers/.

[7]. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., The Path of the Law, 10 Harvard Law Review 457, 467 (1897). Posner, recently retired from the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, was less kind, calling most judges “cagey.” Richard A. Posner, How Judges Think 2 (2008.)

[8]. Cardozo referred to “Some principle, however unavowed and inarticulate and subconscious.” Benjamin N. Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process 1 (1921).

[9]. Id. at 2.

[10]. Posner was more brutally frank: “[M]ost judges are cagey, even coy, in discussing what they do. They tend to parrot an official line about the judicial process.” How Judges Think, supra at 2. He has also criticized avowed “objective” interpretive methodologies for their “remarkable elasticity” to achieve the judge’s desired result. Richard A. Posner, The Incoherence of Antonin Scalia, The New Republic, Aug. 24, 2012. Https://newrepublic.com/article/106441/scalia-garner-reading-the-law-textual-originalism.

[11]. Trump v. Vance, 140 S.Ct. 2412 (2020); Trump v. Mazars, 140 S.Ct. 2019 (2020).

[12]. Trump v. Vance, supra 11

[13]. June Medical Services LLC v. Russo, 140 S.Ct. 2103 (2020).

[14]. June Medical Services L LC v. Gee, 139 S.Ct. 663 (2019).

[15]. Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California, 140 S.Ct. 1891 (2020).

[16]. Id. at 1908.

[17]. Department of Commerce v. New York, 139 S.Ct. 2551, 2576 (2019).

[18]. Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, 140 S.Ct. 1731 (2020).

[19]. Se,e e.g., Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Com’n.,138 S.Ct. 1719, 1735 (2018) (Gorsuch, J., concurring) (Justice Gorsuch arguing that no discrimination at all was involved because the baker would not create a same-sex celebration cake for any couple, same-sex or opposite-sex); and Pavan v. Smith, 137 S.Ct. 2075, 2079 (2017) (Gorsuch, J., dissenting) (Justice Gorsuch arguing for a narrower view of same-sex marriage rights).

[20]. McGirt v. Oklahoma, 140 S.Ct. 2452 (2020).

[21]. Herrera v. Wyoming, 139 S.Ct. 1686 (2019).

[22]. According to calculations in the SCOTUS Blog Final Stat Pack for October Term 2019, which are similar to my own independent figures, Ginsburg was in the majority in 59% of the divided cases, placing her behind Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Kavanaugh, Gorsuch, Kagan, and Breyer, https://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Frequency-in-majority-7.20.20.pdf. According to the same source, she was in the majority in only 3 of the 14 cases decided with a full opinion by a 5–4 vote. Id. at https://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/5-4-cases-7.20.20.pdf.

[23]. The list of these cases, the justices’ votes, and the resulting calculations are the author’s independent work product and are on file with him.

[24]. South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom, 140 S.Ct. 1613 (2020).

In three other major church and state cases this past term, Ginsburg similarly sided with secular societal interests over religion – but in dissent. See Little Sisters of the Poor Saints Peter and Paul Home v. Pennsylvania, 140 S.Ct. 2367 (2020) (contraceptive insurance mandate versus religious objections); Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, 140 S.Ct. 2246 (2020) (church-state separation versus religious support); Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru, 140 S.Ct. 2049 (2020) (anti-discrimination laws versus religious exemptions).

[25].Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo, No. 20A87, November 25, 2020. No further citation is available at this time.

[26]. It should not need to be said, but “politically and socially conservative” versus “politically and socially liberal” are not intended to be proxies for wise or foolish, correct of incorrect, honest or dishonest, or any other variant of right or wrong. As discussed, they are meant solely as the conventions used in public discourse to distinguish positions on issues that typically divide along ideological and partisan grounds.

[27]. Cogitations on Appellate Decision-Making, by The Honorable Hugh R. Jones, The Thirty-Fifth Benjamin N. Cardozo Lecture, delivered before the Association of the Bar of the City of New York on November 28, 1979, https://nycourts.gov/history/legal-history-new-york/documents/History_Jones-Appellate-Decision-Making.pdf. In my view, former New York Court of Appeals Judge Hugh Jones’ articulation of this dissenting phenomenon is unmatched. Here’s a little more of what he said:

[A] dissent permits, indeed invites, a freedom of individual expression and the unveiling of views strongly held . . . . There are instances, too, although perhaps not many in number, in which responsibility to one’s own sense of integrity compels that customary guidelines be ignored and that a dissent be filed-on matters of high principle or instances of deep, irresistible visceral compulsion.

See also the related discussion in Vincent Martin Bonventre, New York’s Chief Judge Kaye: Her Separate Opinions Bode Well for Renewed State Constitutionalism at the New York Court of Appeals, 67 Temple L. Rev. 1163 (1994).

[28]. U.S. v. Uriarte, 975 F.3d 596 (2020).

[29]. 18 U.S.C. § 924.

[30]. United States v. Rutherford, 810 F. Appx. 464 (2019).

[31]. Sims v. Hyatte, 914 F.3d 1078 (2019).

[32]. Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963).

[33]. Judge Barrett’s argument was based on the under the Anti-terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (28 U.S.C. § 2254[d]).

[34]. Schmidt v. Foster, 891 F.3d 302 (2018), vacated en banc, 911 F.3d 469 (2018). The deeply divided en banc ruled that, though the right to counsel might have been violated, there is “not clearly established Supreme Court precedent dictating habeas relief.”

[35]. McCottrell v. White, 933 F.3d 651 (2019).

[36]. Kanter v. Barr, 919 F.3d 437 (2019).

[37]. Cook County, Illinois v. Wolf, 962 F.3d 208 (2020).

[38]. Planned Parenthood of Indiana & Kentucky v. Box, 949 F.3d 997 (2019).

[39]. Planned Parenthood of Indiana & Kentucky v. Commissioner of Indiana State Dept. of Health, 917 F.3d 532 (2018).

[40]. Arlene’s Flowers v. Washington, petition for certiorari filed, Sept. 11 2019.

[41]. Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, petition for certiorari filed, June 15, 2020.

[42]. Association of New Jersey Rifle and Pistol Clubs v. Attorney General New Jersey, No. 19-3142 (3d Cir.), Sept. 1, 2020.

[43]. Ginsburg disagreed that the Second Amendment granted individual gun rights (District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 681 (2008) (joining Justice Breyer’s dissenting opinion)) and that those rights should be assertible against the states (McDonald v. City of Chicago, Ill., 561 U.S. 742, 912 (2010) (joining Justice Breyer’s dissenting opinion)).

[44]. Immigration and Customs Enforcement v. Padilla, petition for certiorari filed, Aug. 24, 2020.

[45]. See, e.g., Nasrallah v. Barr, 140 S.Ct. 1683 (2020) (granting judicial review for an otherwise deportable noncitizen who feared torture).